"Pendant l'été de 1900, je fis la connaissance à Genève d'un garçon de 18 ans, appartenant à une très bonne famille. [...] Ce jeune homme avait contracté au collège des habitudes vicieuses et il les continuait, dans un but intéressé, avec les étrangers de passage à Genève; ne réclamant pour prix de ses complaisances que l'envoi de cartes postales devant enrichir sa collection.

Rentré en France, j'adressai quotidiennement à ce jeune homme, pendant 3 mois, des cartes postales que je choisissais dans les modèles de meilleur goût. Afin de rendre la collection plus intéressante, j'écrivais sur ces cartes postales, de ma plus belle écriture, des vers très délicats, des fragments littéraires et des pensées philosophiques, morales et religieuses: j'avais le soin d'éviter toute citation exprimant trop vivement l'Amour et la passion; le jeune homme était ravi, et il disait à ses parents, qui ne me connaissaient pas, qu'il avait fait connaissance d'un jeune français collectionnant des cartes postales et qu'il échangeait avec lui des cartes suisses pour des cartes françaises.

Les premiers temps, la mère du jeune homme le crut sur parole; mais un beau jour, elle lui déclara formellement qu'il mentait; que ces cartes lui étaient envoyées par une femme, que tout dans l'envoi de ces cartes révélait un être féminin, le bon goût et le choix délicat des cartes et de la littérature, l'élévation des pensées, l'écriture; et qu'il n'arriverait jamais à lui faire croire que c'était un homme qui lui faisait ces envois. "

Extrait de : Charles Double, Etat psychologique et mental d'un inverti parricide, 1905.

dimanche 29 avril 2012

samedi 28 avril 2012

Richard Halliburton and Paul Mooney

"Youth - nothing else worth having in the world…and I had youth, the transitory, the fugitive, now, completely and abundantly. Yet what was I going to do with it? Certainly not squander its gold on the commonplace quest for riches and respectability, and then secretly lament the price that had to be paid for these futile ideals. Let those who wish have their respectability — I wanted freedom, freedom to indulge in whatever caprice struck my fancy, freedom to - search in the farthermost corners of the earth for the beautiful, the joyous and the romantic." (Richard Halliburton, The Royal Road to Romance, 1925)

"Youth - nothing else worth having in the world…and I had youth, the transitory, the fugitive, now, completely and abundantly. Yet what was I going to do with it? Certainly not squander its gold on the commonplace quest for riches and respectability, and then secretly lament the price that had to be paid for these futile ideals. Let those who wish have their respectability — I wanted freedom, freedom to indulge in whatever caprice struck my fancy, freedom to - search in the farthermost corners of the earth for the beautiful, the joyous and the romantic." (Richard Halliburton, The Royal Road to Romance, 1925)"The name of Richard Halliburton, wrote Bobbs Merritt in His Story of His Life's Adventure (1940), is synonymous with youthful adventure. [...]. He was an originator, a trail-blazer whom countless young people have followed and are following. He epitomized their impulses and their dreams - the desire to see the world, the search for the burning moment, for the far horizon, for the unconventional life. [...] With all the wild intensity of his living, Richard Halliburton had also a quiet, studious side. He was refined, cultivated, fastidious. He loved good literature, history, poetry, music. Geography was his passion. He had a rare ability to assimilate knowledge. [...] His great success seemed indeed the glorification of self-expression, but much was never expressed in lecture or the printed page. There he was always the great entertainer, the impersonator. What lay back of the gay and charming exterior?" We learn more about that from Gery Max in Horizon Chasers (1997) : "Linked to his life privately was Paul Mooney (1904-1939). Several years younger than Halliburton, Mooney was a freelance news reporter, travel editor and photo-journalist; he also wrote poetry and told amusing stories. Like Halliburton, he had left school for a time and had hopped a freighter to Europe. If Richard, making a name for himself, had swum the span of the Panama Canal, Paul, emulating Douglas Fairbanks Sr, had leapt from the rooftop of his house to that of a neighbor's next-door and back again. Halliburton hailed from Brownsville, Tennessee, near Memphis. Like Halliburton, Paul was southern, granting that Washington D.C., in the 1900s, was an overgrown sleepy southtern town.

Halliburton attented Princeton - finally graduating - while Mooney attended Catholic University, lasting a semester quitting school about the time the The Royal Road to Romance hit the book stands. As Richard's father, Wesley, of Scottish descent, and harboring a strong work ethic, was a proper southern gentleman with a civil engineering degree from Vanderbilt University, Paul's Father, James Mooney, of Irish descent, was an American Indian authority, of controversial opinion, employed by the Smithsonian Institution. Wesley, very much alive, partly supervised the direction of his son's carreer; James Mooney, dead [in 1921] when Paul [was just sixteen and] may have needed him most, kept only a ghostlike vigilance over his son. By comparison, Paul's mother, Ione, like Halliburton's own mother, Nelle Nance (and surrogate mother Mary Hutchinson, head of the girl's day school Richard attended as a boy), worshipped her son. If Richard feared that a rapid-heart condition would bring him to an early grave, Paul, it is reasonable to suppose, believed the heart condition that killed his father would soon kill him too. Short as each calculated the measure of his life to be, Richard wrung from it rich financial rewards, over a million dollars in his carrer. Paul, no matter the work thrown him, made ends meet, almost, and the plunge the country took into hard times only worsened matters for him.In 1930, when he met Richard, the die of his professional life was cast. Richard wrote in a letter to his father "When my time comes to die, I'll be able to die happy, for I will have done and seen and heard and experienced all the joy, pain thrills - every emotion that any human ever had - and I'll be especially happy if I am spared a stupid, common death in bed."

Halliburton attented Princeton - finally graduating - while Mooney attended Catholic University, lasting a semester quitting school about the time the The Royal Road to Romance hit the book stands. As Richard's father, Wesley, of Scottish descent, and harboring a strong work ethic, was a proper southern gentleman with a civil engineering degree from Vanderbilt University, Paul's Father, James Mooney, of Irish descent, was an American Indian authority, of controversial opinion, employed by the Smithsonian Institution. Wesley, very much alive, partly supervised the direction of his son's carreer; James Mooney, dead [in 1921] when Paul [was just sixteen and] may have needed him most, kept only a ghostlike vigilance over his son. By comparison, Paul's mother, Ione, like Halliburton's own mother, Nelle Nance (and surrogate mother Mary Hutchinson, head of the girl's day school Richard attended as a boy), worshipped her son. If Richard feared that a rapid-heart condition would bring him to an early grave, Paul, it is reasonable to suppose, believed the heart condition that killed his father would soon kill him too. Short as each calculated the measure of his life to be, Richard wrung from it rich financial rewards, over a million dollars in his carrer. Paul, no matter the work thrown him, made ends meet, almost, and the plunge the country took into hard times only worsened matters for him.In 1930, when he met Richard, the die of his professional life was cast. Richard wrote in a letter to his father "When my time comes to die, I'll be able to die happy, for I will have done and seen and heard and experienced all the joy, pain thrills - every emotion that any human ever had - and I'll be especially happy if I am spared a stupid, common death in bed."

At 17, Halliburton had caught a midnight train to New Orleans and signed on as a deckhand on a freighter. He was inspired by Oscar Wilde's book The Picture of Dorian Gray and its warning: "Don't squander the gold of your days... There's such a little time that your youth will last, and you can never get it back! As we grow older our soul gets sick with longing for the things it has forbidden to itself, and our memories are haunted by the exquisite temptations we hadn't the courage to yield to." From there, young Richard went around the world and began his life of adventure and discovery. "I looked behind me at my four [Princeton] roommates bent over their desks dutifully grubbing their lives away", he wrote in The Royal Road to Romance. "John frowned into his public accounting book; he was soon to enter his father’s department store. Penfield yawned over an essay on corporate finance; he planned to sell bonds. Larry was absorbed in protoplasms; his was to be a medical career. Irving (he dreamed sometimes) was struggling unsuccessfully to keep his mind on constitutional government. What futility it all was—stuffing themselves with profitless facts and figures, when the vital and the beautiful things of life – the moonlight, the apple orchards, the out-of-door sirens—were calling and pleading for recognition." Incidentally, he managed to rescue Irving who accompanied him at least in the early stages of the trip.

At 17, Halliburton had caught a midnight train to New Orleans and signed on as a deckhand on a freighter. He was inspired by Oscar Wilde's book The Picture of Dorian Gray and its warning: "Don't squander the gold of your days... There's such a little time that your youth will last, and you can never get it back! As we grow older our soul gets sick with longing for the things it has forbidden to itself, and our memories are haunted by the exquisite temptations we hadn't the courage to yield to." From there, young Richard went around the world and began his life of adventure and discovery. "I looked behind me at my four [Princeton] roommates bent over their desks dutifully grubbing their lives away", he wrote in The Royal Road to Romance. "John frowned into his public accounting book; he was soon to enter his father’s department store. Penfield yawned over an essay on corporate finance; he planned to sell bonds. Larry was absorbed in protoplasms; his was to be a medical career. Irving (he dreamed sometimes) was struggling unsuccessfully to keep his mind on constitutional government. What futility it all was—stuffing themselves with profitless facts and figures, when the vital and the beautiful things of life – the moonlight, the apple orchards, the out-of-door sirens—were calling and pleading for recognition." Incidentally, he managed to rescue Irving who accompanied him at least in the early stages of the trip.

He retraced the route of Ulysses in the Odyssey. He climbed Mt. Fuji in Japan in the middle of winter and the Matterhorn. He descended into the Mayan Well of Death, the Sacred Cenote of Chichen Itza. Occasionally, the trouble he met from authorities only contributed to the drama of his adventures: taking photos of the guns at Gibraltar and being arrested for it as a breach of security; attempting to enter Mecca, which is forbidden to non-Muslims; hiding from gatekeepers on the grounds of the Taj Mahal - to experience in solitude the sunset as well as to swim in the pool facing the tomb under the moonlight... In 1931 Halliburton hired pioneer aviator, Moye W. Stephens (1907-1995) on the strength of a handshake to fly him around the world in an open cockpit biplane named The Flying Carpet. They embarked on "one of the most fantastic, extended air journeys ever recorded" taking 18 months to circumnavigate the globe, covering 33,660 miles, and visiting 34 countries. The two adventurers flew along the Mediterranean coast of France and Spain to Africa and on to Timbuktu. After visiting Legion units in Morocco and Algeria, they flew back to Paris to find a rejection of Halliburton’s request to fly to the ancient city of Samarkand and on east through Soviet Central Asia. They decided to continue around the world by a more southern route. They left on a leisurely flight through Europe, Turkey and the Holy Land, arriving in Cairo. Halliburton had planned a side trip to Abyssinia, but feeling the pressure of time and expenses, dropped the idea, and they took off instead for The Arabian Nights city of Baghdad. Halliburton decided The Flying Carpet should live up to its name by carrying a prince over his realm.

He retraced the route of Ulysses in the Odyssey. He climbed Mt. Fuji in Japan in the middle of winter and the Matterhorn. He descended into the Mayan Well of Death, the Sacred Cenote of Chichen Itza. Occasionally, the trouble he met from authorities only contributed to the drama of his adventures: taking photos of the guns at Gibraltar and being arrested for it as a breach of security; attempting to enter Mecca, which is forbidden to non-Muslims; hiding from gatekeepers on the grounds of the Taj Mahal - to experience in solitude the sunset as well as to swim in the pool facing the tomb under the moonlight... In 1931 Halliburton hired pioneer aviator, Moye W. Stephens (1907-1995) on the strength of a handshake to fly him around the world in an open cockpit biplane named The Flying Carpet. They embarked on "one of the most fantastic, extended air journeys ever recorded" taking 18 months to circumnavigate the globe, covering 33,660 miles, and visiting 34 countries. The two adventurers flew along the Mediterranean coast of France and Spain to Africa and on to Timbuktu. After visiting Legion units in Morocco and Algeria, they flew back to Paris to find a rejection of Halliburton’s request to fly to the ancient city of Samarkand and on east through Soviet Central Asia. They decided to continue around the world by a more southern route. They left on a leisurely flight through Europe, Turkey and the Holy Land, arriving in Cairo. Halliburton had planned a side trip to Abyssinia, but feeling the pressure of time and expenses, dropped the idea, and they took off instead for The Arabian Nights city of Baghdad. Halliburton decided The Flying Carpet should live up to its name by carrying a prince over his realm.

Crown Prince Ghazi of Iraq, a shy, smiling 16-year-old, was eager to fly. His father, King Feisal al Hussein, finally gave in to his pleas but ordered up two RAF planes - carrying the young prince’s uncle and a photographer - as escorts. On their return from a picnic on the ruins of an ancient mosque at Samarra, 75 miles up the Tigris River from Baghdad, Ghazi spotted his military school, where the boys ran out of the classrooms on hearing the low-flying plane. The prince asked Stephens to do some stunts, and the pilot obliged with a slow roll, a wingover and a loop, after which Ghazi went back to school a hero as well as a prince. They continued their trip towards India, Nepal, Malaysia... When they finally came back home, letters from Halliburton’s banker informed him his account was $2,000 overdrawn. He later reckoned he had spent almost $50,000 on his flying adventure and was now broke. Inspired by the exploits of the mighty warrior Hannibal who started to attack Rome with a hundred elephants, Richard Halliburton attempted in 1935 to cross the Alps to Italy on an elephant from the Paris Zoo. Only one of Hannibal's elephants managed to get through - with its ear frozen off - and it seems that Lloyds do not think Halliburton's chances are much brighter because they have charged a premium of 15% on the beast's total value to insure the expedition.

Crown Prince Ghazi of Iraq, a shy, smiling 16-year-old, was eager to fly. His father, King Feisal al Hussein, finally gave in to his pleas but ordered up two RAF planes - carrying the young prince’s uncle and a photographer - as escorts. On their return from a picnic on the ruins of an ancient mosque at Samarra, 75 miles up the Tigris River from Baghdad, Ghazi spotted his military school, where the boys ran out of the classrooms on hearing the low-flying plane. The prince asked Stephens to do some stunts, and the pilot obliged with a slow roll, a wingover and a loop, after which Ghazi went back to school a hero as well as a prince. They continued their trip towards India, Nepal, Malaysia... When they finally came back home, letters from Halliburton’s banker informed him his account was $2,000 overdrawn. He later reckoned he had spent almost $50,000 on his flying adventure and was now broke. Inspired by the exploits of the mighty warrior Hannibal who started to attack Rome with a hundred elephants, Richard Halliburton attempted in 1935 to cross the Alps to Italy on an elephant from the Paris Zoo. Only one of Hannibal's elephants managed to get through - with its ear frozen off - and it seems that Lloyds do not think Halliburton's chances are much brighter because they have charged a premium of 15% on the beast's total value to insure the expedition. "Fair to say, adds Gerry Max, Paul Mooney merged rather than entered into Richard Halliburton's life. Halliburton's life had been at full speed. Enven a thirty, he had begun to weary of travel; even more so, he had begun wearying of writing up into best-selling copy the extensive notes he had taken of his travels. [...] Soon after Richard met Paul Mooney, and the two became lovers, Paul became Richard's principal editor. Paul had inherited oustanding writing skills from his father, whose many technical papers clarified ethnographic topics that other scholars obscured in pedantic gobbledygook. Paul [...] wrote easily in a style that matched Halliburton's own - simple, direct, enthusiastic, interesting. In the course of his ten years relationship with Richard Halliburton, Paul advanced from editor to cowriter of works bearint the Halliburton name. He ghostwrote The Flying Carpet (1932). He also contributed heavily to the content and shape of Seven League Boots (1935) as well as the magazine articles and newspaper columns. [...] He had become an adept ghostwriter, working with the best expression and arrangement of words and ideas without judging too much their meaning. In 1935 he undertook the book I knew Hitler, published by Scribner's, an early study of the dictator then nearing the height of his power in Germany. The book's author was former Nazi diplomat and avowed homosexual Kurt Ledecke, who through rallies in many major American cities and through meetings with prominent American leaders, including Henry Ford, had tried to drum up support to the Nazi cause.

"Fair to say, adds Gerry Max, Paul Mooney merged rather than entered into Richard Halliburton's life. Halliburton's life had been at full speed. Enven a thirty, he had begun to weary of travel; even more so, he had begun wearying of writing up into best-selling copy the extensive notes he had taken of his travels. [...] Soon after Richard met Paul Mooney, and the two became lovers, Paul became Richard's principal editor. Paul had inherited oustanding writing skills from his father, whose many technical papers clarified ethnographic topics that other scholars obscured in pedantic gobbledygook. Paul [...] wrote easily in a style that matched Halliburton's own - simple, direct, enthusiastic, interesting. In the course of his ten years relationship with Richard Halliburton, Paul advanced from editor to cowriter of works bearint the Halliburton name. He ghostwrote The Flying Carpet (1932). He also contributed heavily to the content and shape of Seven League Boots (1935) as well as the magazine articles and newspaper columns. [...] He had become an adept ghostwriter, working with the best expression and arrangement of words and ideas without judging too much their meaning. In 1935 he undertook the book I knew Hitler, published by Scribner's, an early study of the dictator then nearing the height of his power in Germany. The book's author was former Nazi diplomat and avowed homosexual Kurt Ledecke, who through rallies in many major American cities and through meetings with prominent American leaders, including Henry Ford, had tried to drum up support to the Nazi cause.

Paul, meanwhile, advanced from Richard Halliburton's partner to business associate. In short order, they contracted with Paul's friend [and lover] William Alexander [Levy] (1909-1997) to design and build a house for them in Lagun Beach, California." The resulting house came to be known as the Hangover House, a European-inspired, modern masterpiece built of concrete, steel and glass. The house's name had a dual meaning, because it seems to hang over the Aliso Canyon and is a reference to the frequent parties held there. Author Ayn Rand became friends with Levy and visited the house before writing The Fountainhead. In the book, Rand refers to the Heller House, which seems to be a thinly disguised version of the Hangover House. The beach in the lower left corner is Aliso Creek Beach. "Though intended as Richard's principal home, and Paul's, precises Max, it remained in Paul's name. Other changes followed. In the past, Halliburton had traveled mostly by himself. Now he and Paul traveled together, chiefly in America, gathering materials, for an 'American' book? These materials, added to materials from Halliburton's earlier publications, resulted in the two Books of Marvels, The Occident (1937) and The Orient (1938), arguably the single most popular world geography books ever published [...].

Paul, meanwhile, advanced from Richard Halliburton's partner to business associate. In short order, they contracted with Paul's friend [and lover] William Alexander [Levy] (1909-1997) to design and build a house for them in Lagun Beach, California." The resulting house came to be known as the Hangover House, a European-inspired, modern masterpiece built of concrete, steel and glass. The house's name had a dual meaning, because it seems to hang over the Aliso Canyon and is a reference to the frequent parties held there. Author Ayn Rand became friends with Levy and visited the house before writing The Fountainhead. In the book, Rand refers to the Heller House, which seems to be a thinly disguised version of the Hangover House. The beach in the lower left corner is Aliso Creek Beach. "Though intended as Richard's principal home, and Paul's, precises Max, it remained in Paul's name. Other changes followed. In the past, Halliburton had traveled mostly by himself. Now he and Paul traveled together, chiefly in America, gathering materials, for an 'American' book? These materials, added to materials from Halliburton's earlier publications, resulted in the two Books of Marvels, The Occident (1937) and The Orient (1938), arguably the single most popular world geography books ever published [...]. Intellectual, Paul was alto athletic. He was prickly, and, as he said himself, 'temperamental as hell', but he was never tedious or insipid. He sulked, but never whined. When he first left home, Paul, like Richard, was a happy thrill-seeker. Like the poet Rupert Brooke, he had an 'itching heel', preferred the outdoors, 'showed a reluctance to conform' and had a 'gypsy-like idleness'. While Richard saw money as something to be amassed, Paul seemed embarrassed to have it in his pocket for too long. He read a good deal. He listened to stories. He liked speedy cars. Aviation fascinated him. He once hopped a freighter bound for Constantinople. He loafed around Paris. [...]. He wrote poems. Privately printed in 1927, these poems offer some testimony that he was a devoted fan of Richard Halliburton long before he met him." About 1930, Paul drives off to California where, maybe at one of Halliburton's much publicized lectures , or at a party of aviation aficionados and Hollywood stars, he meets celebrity Richard Halliburton and the two hit it off. "Once they met, Paul became everything, or nearly everything, to Richard. To the extent that Paul chauffeured him to and from the airport, dragged him down to the beach for his 'celebrity' tan, and nursed him back to health when he was sick, Paul always remained, in a sense, Richard's man-servant, and confidant. He also remained Richard's principal friend an love interest, though neither Richard nor Paul maintained any more fidelity to monogamy than they did to single authorship of one of Richard Halliburton's books.[...] By the end of 1930s, the Depression had sapped much of his zest for life. He had begun to see the sham, as some of his letters make clear, and found it hard to pretend he didn't. He grew cynical, he began to mope, overindulging his love of drinking and smoking. In 1938, two years after the idea for the project commenced, Richard requested that Paul join him in attempting to sail a Chinese junk from Hong Kong to the Golden Gate International Exposition [...]. The first overseas trip they would make together, it was also the last." Richard and Paul sailed in The Sea Dragon crewed by Cornell undergraduates and skippered by an Australian alcoholic. They negotiated the Japanese blockade but ran into a storm four days out. Their last radio message was '…storm, but no problem.' Searching U.S. Navy ships and aircraft found no trace of them. During 1945, some wreckage identified as a rudder and believed to belong to the Sea Dragon washed ashore in California. "After his son's death, Wesley Halliburton did the best he could to remove any references to Paul (among others) in Richard's soon-be-published letters. Though it was prudent to omit such references, no trace of intimacy between Paul and Richard is even implied - their own letters to one another are lost."

Intellectual, Paul was alto athletic. He was prickly, and, as he said himself, 'temperamental as hell', but he was never tedious or insipid. He sulked, but never whined. When he first left home, Paul, like Richard, was a happy thrill-seeker. Like the poet Rupert Brooke, he had an 'itching heel', preferred the outdoors, 'showed a reluctance to conform' and had a 'gypsy-like idleness'. While Richard saw money as something to be amassed, Paul seemed embarrassed to have it in his pocket for too long. He read a good deal. He listened to stories. He liked speedy cars. Aviation fascinated him. He once hopped a freighter bound for Constantinople. He loafed around Paris. [...]. He wrote poems. Privately printed in 1927, these poems offer some testimony that he was a devoted fan of Richard Halliburton long before he met him." About 1930, Paul drives off to California where, maybe at one of Halliburton's much publicized lectures , or at a party of aviation aficionados and Hollywood stars, he meets celebrity Richard Halliburton and the two hit it off. "Once they met, Paul became everything, or nearly everything, to Richard. To the extent that Paul chauffeured him to and from the airport, dragged him down to the beach for his 'celebrity' tan, and nursed him back to health when he was sick, Paul always remained, in a sense, Richard's man-servant, and confidant. He also remained Richard's principal friend an love interest, though neither Richard nor Paul maintained any more fidelity to monogamy than they did to single authorship of one of Richard Halliburton's books.[...] By the end of 1930s, the Depression had sapped much of his zest for life. He had begun to see the sham, as some of his letters make clear, and found it hard to pretend he didn't. He grew cynical, he began to mope, overindulging his love of drinking and smoking. In 1938, two years after the idea for the project commenced, Richard requested that Paul join him in attempting to sail a Chinese junk from Hong Kong to the Golden Gate International Exposition [...]. The first overseas trip they would make together, it was also the last." Richard and Paul sailed in The Sea Dragon crewed by Cornell undergraduates and skippered by an Australian alcoholic. They negotiated the Japanese blockade but ran into a storm four days out. Their last radio message was '…storm, but no problem.' Searching U.S. Navy ships and aircraft found no trace of them. During 1945, some wreckage identified as a rudder and believed to belong to the Sea Dragon washed ashore in California. "After his son's death, Wesley Halliburton did the best he could to remove any references to Paul (among others) in Richard's soon-be-published letters. Though it was prudent to omit such references, no trace of intimacy between Paul and Richard is even implied - their own letters to one another are lost."

Gay stars and wisecrackers in Hollywood 1910-1930

One of the most fascinating figures of the silent era was the now forgotten [George] J[ack] Warren Kerrigan (1879-1947). When this first major gay star in Hollywood told Shadowland (October 1919) of "leading a double life", he was referencing his Irish heritage demanding a life of wandering, fighting, and adventure when, in reality, he longed for a quiet home life. Interested in the arts, showing promise in both singing and acting, young Jack also liked to paint and write. He began appearing in community theater in the New Albany and Louisville area around the age of 18, while working at his father's warehouse and attending school. He concentrated more and more on acting, making his New York stage debut in 1906. Other productions followed as Jack developed into a leading man. It was at this time that Jack became known as "The Gibson Man", so named because he was as handsome as a Gibson Girl was beautiful. "I [...] received an offer from a man in the employ of the Vitagraph in New York, but I was doing well on the legitimate stage at that time and the matter was dropped. Later, while playing in Chicago in The Road to Yesterday, a member of the Essanay made me an offer to join their company. It took me some time to overcome the prejudices of stage folk and to realize that the motion picture theater was the greatest institution for the entertainment of all the people in the world. The screen covers an unlimited field. After a month’s work before the camera, I decided that I had found my vocation. My 'up-stage' opinions faded away and I realized that a great new school of acting, comprehending unlimited possibilities, had originated in motion pictures. [...] Upon the organization of the American Company, I was the first member to be engaged. For a period of three years I played lead in every picture - sometimes at the rate of two a week - which that company produced." He joined Universal in 1913, starring in length movies, as Samson in 1914.

One of the most fascinating figures of the silent era was the now forgotten [George] J[ack] Warren Kerrigan (1879-1947). When this first major gay star in Hollywood told Shadowland (October 1919) of "leading a double life", he was referencing his Irish heritage demanding a life of wandering, fighting, and adventure when, in reality, he longed for a quiet home life. Interested in the arts, showing promise in both singing and acting, young Jack also liked to paint and write. He began appearing in community theater in the New Albany and Louisville area around the age of 18, while working at his father's warehouse and attending school. He concentrated more and more on acting, making his New York stage debut in 1906. Other productions followed as Jack developed into a leading man. It was at this time that Jack became known as "The Gibson Man", so named because he was as handsome as a Gibson Girl was beautiful. "I [...] received an offer from a man in the employ of the Vitagraph in New York, but I was doing well on the legitimate stage at that time and the matter was dropped. Later, while playing in Chicago in The Road to Yesterday, a member of the Essanay made me an offer to join their company. It took me some time to overcome the prejudices of stage folk and to realize that the motion picture theater was the greatest institution for the entertainment of all the people in the world. The screen covers an unlimited field. After a month’s work before the camera, I decided that I had found my vocation. My 'up-stage' opinions faded away and I realized that a great new school of acting, comprehending unlimited possibilities, had originated in motion pictures. [...] Upon the organization of the American Company, I was the first member to be engaged. For a period of three years I played lead in every picture - sometimes at the rate of two a week - which that company produced." He joined Universal in 1913, starring in length movies, as Samson in 1914. His career was then managed by his twin brother Wallace Kerrigan. It was also in 1914 that Jack published his autobiography, becoming the first motion picture star to do so. A song was also written about him in 1914, titled (modestly enough) The Hero of Them All. Photoplay, conducting in 1913 a popularity contest among its readers, named him the most popular male star - a very special male star, handsome but effeminate, fun loving, who lived with his mother (and his partner) in "The Kumfy Kerrigan Kottage" and once told the Motion Picture Blue Book that he loved the ladies "when they leave me alone." His career was almost ruined in 1917 when he told a local Denver newspaper that he would not go to war and that first American should take "the great mass of men who aren't good for anything". He argued that those who brought beauty to the world, such as the actor, should not be drafted. In August 1917, Photoplay's James R. Quirk brought Kerrigan's outlook to his readership, branding the actor as "one of the beautiful slackers". For scriptwriter and director Allan Dwan, J. Warren Kerrigan was "quite a lady himself", and he said there were many such "pansies and poseurs" because "Hollywood sucked them all".

His career was then managed by his twin brother Wallace Kerrigan. It was also in 1914 that Jack published his autobiography, becoming the first motion picture star to do so. A song was also written about him in 1914, titled (modestly enough) The Hero of Them All. Photoplay, conducting in 1913 a popularity contest among its readers, named him the most popular male star - a very special male star, handsome but effeminate, fun loving, who lived with his mother (and his partner) in "The Kumfy Kerrigan Kottage" and once told the Motion Picture Blue Book that he loved the ladies "when they leave me alone." His career was almost ruined in 1917 when he told a local Denver newspaper that he would not go to war and that first American should take "the great mass of men who aren't good for anything". He argued that those who brought beauty to the world, such as the actor, should not be drafted. In August 1917, Photoplay's James R. Quirk brought Kerrigan's outlook to his readership, branding the actor as "one of the beautiful slackers". For scriptwriter and director Allan Dwan, J. Warren Kerrigan was "quite a lady himself", and he said there were many such "pansies and poseurs" because "Hollywood sucked them all".

Young William Haines (1900-1973) ran away from home at the age of 14 with his "boyfriend" and worked in a dance hall which may have also served as a brothel. He was an assistant bookkeeper at a New York bond house when he sent in his photograph to a "New Faces" contest sponsored by movie producer Samuel Goldwyn in 1922. After a successful screen test, he was signed as a contract player; and in 1922 he departed for California. It was in Brown of Harvard (1926) that he crystallized his screen image, a young arrogant man who is humbled by the last reel. "He has never been in love with any girl yet, and doesn’t intend to", stated fan magazines. In 1926, Bill Haines fell in love for twenty-one-year-old Jimmie Shields (1905-1974), who he met in New York probably as a pick-up on the street. They moved in together and became, as Joan Crawford once said, "the happiest married couple in Hollywood". Shields was put on the MGM payroll as Bill's secretary and stand-in. The two stayed together for nearly fifty years, until Bill's death. Haines was the perfect male flapper for the latter half of the 1920s. While Valentino represented the dangerous love and John Gilbert played noble, tortured heroes, Haines exemplified the sunny, collegiate self-confidence of jazz Age. His screen heroes were the happy-go-lucky fellows his fans thought themselves to be. And Bill's generally cheery offscreen personality fitted perfectly with this. In 1933, Billy Haines picked up a sailor in Pershing Square in Los Angeles and took him to the YMCA where he had a room. The house detective and L.A. Vice Squad burst in and arrested and handcuffed both men. Losing his boyish good looks after age 30, Haines accepted the decline of his star with grace. Battles with Louis B. Mayer over his "scandalous" love life finally ended his career in 1934. After that, tasteful Haines became a famous interior decorator.

Young William Haines (1900-1973) ran away from home at the age of 14 with his "boyfriend" and worked in a dance hall which may have also served as a brothel. He was an assistant bookkeeper at a New York bond house when he sent in his photograph to a "New Faces" contest sponsored by movie producer Samuel Goldwyn in 1922. After a successful screen test, he was signed as a contract player; and in 1922 he departed for California. It was in Brown of Harvard (1926) that he crystallized his screen image, a young arrogant man who is humbled by the last reel. "He has never been in love with any girl yet, and doesn’t intend to", stated fan magazines. In 1926, Bill Haines fell in love for twenty-one-year-old Jimmie Shields (1905-1974), who he met in New York probably as a pick-up on the street. They moved in together and became, as Joan Crawford once said, "the happiest married couple in Hollywood". Shields was put on the MGM payroll as Bill's secretary and stand-in. The two stayed together for nearly fifty years, until Bill's death. Haines was the perfect male flapper for the latter half of the 1920s. While Valentino represented the dangerous love and John Gilbert played noble, tortured heroes, Haines exemplified the sunny, collegiate self-confidence of jazz Age. His screen heroes were the happy-go-lucky fellows his fans thought themselves to be. And Bill's generally cheery offscreen personality fitted perfectly with this. In 1933, Billy Haines picked up a sailor in Pershing Square in Los Angeles and took him to the YMCA where he had a room. The house detective and L.A. Vice Squad burst in and arrested and handcuffed both men. Losing his boyish good looks after age 30, Haines accepted the decline of his star with grace. Battles with Louis B. Mayer over his "scandalous" love life finally ended his career in 1934. After that, tasteful Haines became a famous interior decorator.

As early as November 1929, Katharine Albert explained in Photoplay "How bachelors manage their homes". Described as a "playboy", William Haines appeared in a photograph captioned "at home, fastidious housekeeper and host, art connoisseur. The commode is Venetian, the portrait a Sir Peter Lely." Tea with Ramon Novarro was served by his "man" (Novarro's "valet" and éminence grise Frank Hansen) and consisted of "tiny finger sandwiches, chut in hearts and shamrocks, and luscious little petit fours" and that Gary Cooper (1901-1961) lived with his mother. She noted a banling ham in the kitchen, a gift from Andy Lawlor's mother in Virginia. Modern research suggest overwhelmingly that Coooper was involved in a long-term relationship with Andy Lawlor aka Anderson Lawler (1902-1959).

Just arrived in Hollywood, where he met Cooper, Lawler acted in thirty-nine films over the next ten years, his last film credit being in 1939. Seventeen of those roles however were uncredited bit parts, and in addition one role was deleted before the film was published. Lawler frequently stayed at the Cooper house at 7511 Franklin Avenue while Cooper's parents were away. When Cooper eventually took his own apartment on Argyle Avenue, Anderson casually moved in...

Gary Cooper was featured in a November 1930 Picture Play photo section headed "Boys will be boys", in which, it was explained, our virile heroes assume expressions that belong to ingénues. The photograph published must be the most effeminate ever taken of the rugged leading man? Coming a close second was David Rollins (1897-1997), of whom it was explained, "he has been coy and coquettish in so many photographs that this is no novelty."

Among the other ''wisecrackers'' (1920s slang for gay) was Harrison Ford (1884-1957), who was reported going in a costume-buying spree for actress Norma Talmadge and being "as enthusiastic as a young debutante planning her first party dress." The actor rarely gave interviews and only talked about his professional, not private, life, so little is known of his background. An article states that he left school at fourteen to join a stock company, working his way up from stagehand to bit player. "A rather serious, secretive chap", one reporter called him. "The Hermit of Hollywood" soon became his nickname. "When discussing a question", wrote journalist William McKegg, "Mr. Ford has the trick of looking far away, or down on the ground, or glancing behind him, as though he might find the explanation in any of these directions." Harrison himself complained, "What I can't make out, though, is what you people see in any of us [actors] interesting enough to keep writing about." If Harrison had any romance, it remained unreported. The few private glimpses into his life involved his love of gardening and his large collection of books, many of them first editions.

Among the other ''wisecrackers'' (1920s slang for gay) was Harrison Ford (1884-1957), who was reported going in a costume-buying spree for actress Norma Talmadge and being "as enthusiastic as a young debutante planning her first party dress." The actor rarely gave interviews and only talked about his professional, not private, life, so little is known of his background. An article states that he left school at fourteen to join a stock company, working his way up from stagehand to bit player. "A rather serious, secretive chap", one reporter called him. "The Hermit of Hollywood" soon became his nickname. "When discussing a question", wrote journalist William McKegg, "Mr. Ford has the trick of looking far away, or down on the ground, or glancing behind him, as though he might find the explanation in any of these directions." Harrison himself complained, "What I can't make out, though, is what you people see in any of us [actors] interesting enough to keep writing about." If Harrison had any romance, it remained unreported. The few private glimpses into his life involved his love of gardening and his large collection of books, many of them first editions.

Another gay star was Gareth Hughes (1897-1965), who had the lead in Fox's Every Mother's Son in 1918. As a young Welsh actor, his career began in 1919. The writer Fulton Oursler called him "the charm boy to end all charm boys." There seems little doubt, regardless of his angelic face, that he had a great deal of fun in the pre-code days. "The exuberance of the men and women about me impresses me deeply", he confessed to a journalist. Actress Viola Dana told historian Anthony Slide that several actress's refused to kiss him because he was so sexually active. The big question is - active with whom? Asked in 1921 by a journalist if he is married, Hughes says he is not and "he never will be. But then, you see, he is only 22. It's just a phase of youth." Gareth continued working in film in Hollywood until 1929, going back to Broadway briefly in 1925 to perform in "The Dunce Boy". After 1929 he went back to the theater, but he continued to keep a residence in Los Angeles and lived with a number of people during the 1930s. One of these, in 1936 according to Voter Registration records, was an interior decorator named Myron L. Gray. Hughes lived out his days productively as a member of an Episcopal monastery who worked with Paiute Indians in Nevada.

Another gay star was Gareth Hughes (1897-1965), who had the lead in Fox's Every Mother's Son in 1918. As a young Welsh actor, his career began in 1919. The writer Fulton Oursler called him "the charm boy to end all charm boys." There seems little doubt, regardless of his angelic face, that he had a great deal of fun in the pre-code days. "The exuberance of the men and women about me impresses me deeply", he confessed to a journalist. Actress Viola Dana told historian Anthony Slide that several actress's refused to kiss him because he was so sexually active. The big question is - active with whom? Asked in 1921 by a journalist if he is married, Hughes says he is not and "he never will be. But then, you see, he is only 22. It's just a phase of youth." Gareth continued working in film in Hollywood until 1929, going back to Broadway briefly in 1925 to perform in "The Dunce Boy". After 1929 he went back to the theater, but he continued to keep a residence in Los Angeles and lived with a number of people during the 1930s. One of these, in 1936 according to Voter Registration records, was an interior decorator named Myron L. Gray. Hughes lived out his days productively as a member of an Episcopal monastery who worked with Paiute Indians in Nevada.

Stephen Tennant and the cruising dandies

Among the myths associated with the 1920s, the flamboyance of style is the most persistent. [...] Most homosexuals wanted [...] to blend in with the mass of "normal" people and so they conformed to the canons of virility that were in vogue at the timen adding only the slightest variations to their appearance. [...] The "serious, intelligent and embarrassed homosexual" dit not distinguish himself in any way. The hair was worn very short at the nape of the neck and on the sides, brillantined and combed in order to form a wave or plastered smooth like patent leather. The suit was dark, of thick fabric, broad in cut, with the bottom of the trousers flared. This baggy fashion had some erotic advantages, as Gifford Skinner relates : "The average man wore his trousers very full cut and they went up almost to the chest. The underclothers, if one wore any, were quite as loose and left the genitals free. Any friction caused by walking could produce the most stark effect. In the street, homosexuals would stud their conversation with remarks like 'Did you see that piece?' or 'Look what's coming - he's sticking straight out!' This was often an illusion caused by a fold in the clothing, but it was a pleasant pastime and didn't cost anything."

Among the myths associated with the 1920s, the flamboyance of style is the most persistent. [...] Most homosexuals wanted [...] to blend in with the mass of "normal" people and so they conformed to the canons of virility that were in vogue at the timen adding only the slightest variations to their appearance. [...] The "serious, intelligent and embarrassed homosexual" dit not distinguish himself in any way. The hair was worn very short at the nape of the neck and on the sides, brillantined and combed in order to form a wave or plastered smooth like patent leather. The suit was dark, of thick fabric, broad in cut, with the bottom of the trousers flared. This baggy fashion had some erotic advantages, as Gifford Skinner relates : "The average man wore his trousers very full cut and they went up almost to the chest. The underclothers, if one wore any, were quite as loose and left the genitals free. Any friction caused by walking could produce the most stark effect. In the street, homosexuals would stud their conversation with remarks like 'Did you see that piece?' or 'Look what's coming - he's sticking straight out!' This was often an illusion caused by a fold in the clothing, but it was a pleasant pastime and didn't cost anything." Others, however, sought a departure from the ubiquitous classicism. Suits in electric blue, almond green or old rose were much admired, but few dared to wear them for fear of being kicked out of public places. Certain accessories became homosexual signs of recognition, in particular suede shoes and camel's hair coats. Some dared to wear their hair long. Any eccentricity was readily perceived as proof of inversion, leading to a little adventure for Quentin Crisp, a flagrant homosexual if ever there was one, when he presented himself at the draft board : While his eyes were being tested, they said to him, "You've dyed your hair. That's a sign of sexual perversion. Do you know what these words mean?" He just said yes, and that he was a homosexual. That does not mean that the man in the street could clearly identify a homosexual that he knew enough to decipher the signs. However, any sartorial oddity was suspicious and could easily be seen as a sign of homosexuality. There was one way out : to be perceived as an artist, i.e. necessarily an "original". Crisp notes that the sexual significance of certain forms of comportment was understood only vaguely, but the sartorial symbolism was recognized by everyone. Wearing suede shoes inevitably made you suspect. Anyone whose hair was a little raggedy at the nape of the neck was regarded as an artist, a foreigner, or worse yet. One of his friends told him that, when someone introduced him to an older gentleman as an artist, the man said : "Oh, I know his young man is an artist. The other day I saw him on the street in a brown jacket." In the same way, the use of make-up was spreading, so that mere possession of a powder puff was enough to prove one's homosexuality for the police.

Others, however, sought a departure from the ubiquitous classicism. Suits in electric blue, almond green or old rose were much admired, but few dared to wear them for fear of being kicked out of public places. Certain accessories became homosexual signs of recognition, in particular suede shoes and camel's hair coats. Some dared to wear their hair long. Any eccentricity was readily perceived as proof of inversion, leading to a little adventure for Quentin Crisp, a flagrant homosexual if ever there was one, when he presented himself at the draft board : While his eyes were being tested, they said to him, "You've dyed your hair. That's a sign of sexual perversion. Do you know what these words mean?" He just said yes, and that he was a homosexual. That does not mean that the man in the street could clearly identify a homosexual that he knew enough to decipher the signs. However, any sartorial oddity was suspicious and could easily be seen as a sign of homosexuality. There was one way out : to be perceived as an artist, i.e. necessarily an "original". Crisp notes that the sexual significance of certain forms of comportment was understood only vaguely, but the sartorial symbolism was recognized by everyone. Wearing suede shoes inevitably made you suspect. Anyone whose hair was a little raggedy at the nape of the neck was regarded as an artist, a foreigner, or worse yet. One of his friends told him that, when someone introduced him to an older gentleman as an artist, the man said : "Oh, I know his young man is an artist. The other day I saw him on the street in a brown jacket." In the same way, the use of make-up was spreading, so that mere possession of a powder puff was enough to prove one's homosexuality for the police.

[...] The very chic Stephen Tenant (1906-1987), taking tea with his aunt, was admonished : "Stephen darling, go and wash your face." Thus we know that the practice was by no means limited to male prostitutes, but involved various social classes. However, it was far from being well accepted, even in the most exalted circles. At a ball hosted by the Earl of Pembroke, Cecil Beaton was thrown in the water by some of the more virile young men; one of them shouted : " Do you think the fag drowned?" According to Tennant, who was there at the time, the attack was caused by the abuse of make-up ; he was convinced that it was Beaton's made-up that so disturbed the thugs. When Stephen Tennant was a little boy in Edwardian England, his father asked him what he would like to be when he grew up. "I want to be a Great Beauty, Sir," he replied. In the 1920s, Stephen Tennant embodied homosexual aesthetics carried to its apogee. He was a great beauty, and he enjoyed using all the artifices of seduction and l'art de la pose, theatricality. In that, he exaggerated the prevailing fashion for dressing up.[...] Photographed by Cecil Beaton, especially, Tennant looked like a prince charming. Even in his everyday wear, he stood apart from the crowd ; [...] his style and his innate sense of theater [...] made him a symbol of the Bright Young People of the 1920s in London. Late in the decade, Tennant represented the most extrem of fashion - for a man, at least. His feminine manners and appearance were not diminished by the striped double-breasted suits he wore, in good taste and well cut, "which ought to have made him resemble any young fellow downtown." But Stephen's physical presence was enough to belie such an impression. He was large and imperious, but he moved with a pronounced step, affected, which was drescribed as "prancing" or as "seeming to be attached at the knees".

[...] The very chic Stephen Tenant (1906-1987), taking tea with his aunt, was admonished : "Stephen darling, go and wash your face." Thus we know that the practice was by no means limited to male prostitutes, but involved various social classes. However, it was far from being well accepted, even in the most exalted circles. At a ball hosted by the Earl of Pembroke, Cecil Beaton was thrown in the water by some of the more virile young men; one of them shouted : " Do you think the fag drowned?" According to Tennant, who was there at the time, the attack was caused by the abuse of make-up ; he was convinced that it was Beaton's made-up that so disturbed the thugs. When Stephen Tennant was a little boy in Edwardian England, his father asked him what he would like to be when he grew up. "I want to be a Great Beauty, Sir," he replied. In the 1920s, Stephen Tennant embodied homosexual aesthetics carried to its apogee. He was a great beauty, and he enjoyed using all the artifices of seduction and l'art de la pose, theatricality. In that, he exaggerated the prevailing fashion for dressing up.[...] Photographed by Cecil Beaton, especially, Tennant looked like a prince charming. Even in his everyday wear, he stood apart from the crowd ; [...] his style and his innate sense of theater [...] made him a symbol of the Bright Young People of the 1920s in London. Late in the decade, Tennant represented the most extrem of fashion - for a man, at least. His feminine manners and appearance were not diminished by the striped double-breasted suits he wore, in good taste and well cut, "which ought to have made him resemble any young fellow downtown." But Stephen's physical presence was enough to belie such an impression. He was large and imperious, but he moved with a pronounced step, affected, which was drescribed as "prancing" or as "seeming to be attached at the knees".

Each of his movements, from the facial muscles to his long limbs, seemed calculated for effect. He gilded his fair hair with a sprinkling of gold dust, and used certain preparations to hold the dark roots in check. "Stephen could very well have been taken for a Vogue illustration - perhaps by Lepappe - brought to life." [...] Together with Cecil Beaton, Stephen Tennant and other young society men organized all kinds of themed evenings. Stephen Tennant's effeminate appearance caused ambivalent reactions. Some were simply struck : "I do not know if that is a man or a woman, but it is the most beautiful creature I have ever seen", the admiral Sir Lewis Clinton-Baker would say. Others were less indulgent. When Tennant arrived one evening dressed particularly outrageously, the criticism reached a boiling point. Rex Whistler, one of his friends, considered it regrettable that he had gone too far : "He posed as much as a girl." Rex's brother added, "Men should not draw attention to themselves. That was the only true charge against Stephen, and it was irrefutable." Parents also complained that their children spent time with Stephen. Edith Olivier noted that Helena Folkestone was complaining about how badly people spoke of Stephen, that he was hated by people who did not understand him. Olivier noted that they were out of touch with the times, since "nowadays so many boys resemble girls without being effeminate. That is the kind of boys that have grown up since the war."

Each of his movements, from the facial muscles to his long limbs, seemed calculated for effect. He gilded his fair hair with a sprinkling of gold dust, and used certain preparations to hold the dark roots in check. "Stephen could very well have been taken for a Vogue illustration - perhaps by Lepappe - brought to life." [...] Together with Cecil Beaton, Stephen Tennant and other young society men organized all kinds of themed evenings. Stephen Tennant's effeminate appearance caused ambivalent reactions. Some were simply struck : "I do not know if that is a man or a woman, but it is the most beautiful creature I have ever seen", the admiral Sir Lewis Clinton-Baker would say. Others were less indulgent. When Tennant arrived one evening dressed particularly outrageously, the criticism reached a boiling point. Rex Whistler, one of his friends, considered it regrettable that he had gone too far : "He posed as much as a girl." Rex's brother added, "Men should not draw attention to themselves. That was the only true charge against Stephen, and it was irrefutable." Parents also complained that their children spent time with Stephen. Edith Olivier noted that Helena Folkestone was complaining about how badly people spoke of Stephen, that he was hated by people who did not understand him. Olivier noted that they were out of touch with the times, since "nowadays so many boys resemble girls without being effeminate. That is the kind of boys that have grown up since the war."

Although many who knew Tennant later in life "could hardly believe the physical act possible for him", The one real love affair of his adult life was with Siegfried Sassoon (1886-1967), the masculine, renowned pacifist poet. Sassoon brought to their relationship his fame, his talent, his position, while Tennant's only daily activities were dressing-up and reading about himself in the gossip columns. Looking at the photos of the two lovers, Tennant posing languidly (vogueing, really), way-too-thin and way-too-rich, as Sassoon looks on proudly, even the most radical Act-Up militant might mutter a private "Oh, brother!" However Tennant's extreme elegance was close to sexual terrorism, as it flabbergasted society on both sides of the Atlantic for half a century. "Cherish me and introduce me to the glories of New York," Tennant telephoned a startled friend, David Herbert, as he crossed the Atlantic on the Berengaria. Herbert met Tennant at the boat and was embarrassed to see him walking down the gangway "marcelled and painted [...] delicately holding a spray of cattleya orchids."Pin 'em on!" shouted a tough customs officer in homophobic disgust."Oh, have you got a pin?" exclaimed Tennant in complete disregard for the reaction of others. "You kind, kind creature."

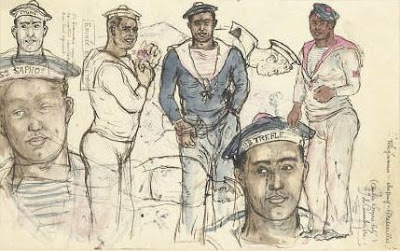

Although many who knew Tennant later in life "could hardly believe the physical act possible for him", The one real love affair of his adult life was with Siegfried Sassoon (1886-1967), the masculine, renowned pacifist poet. Sassoon brought to their relationship his fame, his talent, his position, while Tennant's only daily activities were dressing-up and reading about himself in the gossip columns. Looking at the photos of the two lovers, Tennant posing languidly (vogueing, really), way-too-thin and way-too-rich, as Sassoon looks on proudly, even the most radical Act-Up militant might mutter a private "Oh, brother!" However Tennant's extreme elegance was close to sexual terrorism, as it flabbergasted society on both sides of the Atlantic for half a century. "Cherish me and introduce me to the glories of New York," Tennant telephoned a startled friend, David Herbert, as he crossed the Atlantic on the Berengaria. Herbert met Tennant at the boat and was embarrassed to see him walking down the gangway "marcelled and painted [...] delicately holding a spray of cattleya orchids."Pin 'em on!" shouted a tough customs officer in homophobic disgust."Oh, have you got a pin?" exclaimed Tennant in complete disregard for the reaction of others. "You kind, kind creature." In London, sollicitation principally took the form of "cottaging"; it consisted in making the rounds of the various urinals of the city looking for quick and anonymous meetings. [...] The urinals were frequently subjected to police raids; and there were often agents provocateurs, which made it all the more dangerous. Then other places were used used as pick-up sites, like the arcades of the County Fire Office in Piccadilly Circus, the Turkish baths at Jermyn Street, the isolated streets [...] ; in Clareville Street, Leicester Public garden or Grosvenor Hill, one could find somebody for the night. [...] As in Germany, but to a lesser degree, male prostitution expanded tue to unemployment. At the Cat and Flute in Charing Cross, young workmen would be found. The contemporary practice was that two would sit together and share a beer. A client would approach and offer to pay for the second one. After a moment one of the boys would step away, leaving the two others together. These boys were not necessarily homosexual, but got into prostitution due to the econoic situation. Some of them said they were "saving up to get married." The rates were set, with 10 shillings added if there were sodomy. Soldiers (mainly from the Guards brigad) and sailors made up another category of prostitutes. Unlike the workmen, they were not in prostitution as a result of need but rather by tradition. The best places to meet them were the London parks, [...] Tattersall Tavern in Knightsbridge, and The Drum, by the Tower of London, for sailors. The guards' red uniform and the sailors' costumes exerted a fascination and an erotic attraction that was constantly evoked by contemporaries: "everyone prefers something in uniform." Any national costume or traditional equipment can be sexually stimulating and there are as many eccentric sexual tastes as there are kinds of costumes.

In London, sollicitation principally took the form of "cottaging"; it consisted in making the rounds of the various urinals of the city looking for quick and anonymous meetings. [...] The urinals were frequently subjected to police raids; and there were often agents provocateurs, which made it all the more dangerous. Then other places were used used as pick-up sites, like the arcades of the County Fire Office in Piccadilly Circus, the Turkish baths at Jermyn Street, the isolated streets [...] ; in Clareville Street, Leicester Public garden or Grosvenor Hill, one could find somebody for the night. [...] As in Germany, but to a lesser degree, male prostitution expanded tue to unemployment. At the Cat and Flute in Charing Cross, young workmen would be found. The contemporary practice was that two would sit together and share a beer. A client would approach and offer to pay for the second one. After a moment one of the boys would step away, leaving the two others together. These boys were not necessarily homosexual, but got into prostitution due to the econoic situation. Some of them said they were "saving up to get married." The rates were set, with 10 shillings added if there were sodomy. Soldiers (mainly from the Guards brigad) and sailors made up another category of prostitutes. Unlike the workmen, they were not in prostitution as a result of need but rather by tradition. The best places to meet them were the London parks, [...] Tattersall Tavern in Knightsbridge, and The Drum, by the Tower of London, for sailors. The guards' red uniform and the sailors' costumes exerted a fascination and an erotic attraction that was constantly evoked by contemporaries: "everyone prefers something in uniform." Any national costume or traditional equipment can be sexually stimulating and there are as many eccentric sexual tastes as there are kinds of costumes. The sailors' uniform was particularly appreciated for the tight fit and especially for the horizontal fly. Moreover, while soldiers generally had very little time to share, sailors had many weekends. For a walk in the park, a soldier received about 2 shillings ; a silor might get up to 3 pounds. Stephen Tennant wrote about this fascination, nothing one sailor's tight little derière. Anecdotes from those days include the story of an evening organized by Edward Gathorne-Hardy where a contingent of soldiers of the Guard were invited as special guests ; in another, a soldier was offered as a gift to the master of the house. To the soldiers, prostitution was a tradition ; it seems that the young recruits were initiated by the elders as they were being integrated into the regiment. The customers were designated twanks, steamers or fitter's mates. A good patron was preferred ; thus Ackerley reveived a letter one day announcing the death of one of his lovers - and another soldier from his regiment offering himself as a replacement. This part-time prostitution allowed soldiers to get some pocket money, which they then spent on drinks or with prostitutes of their own. These activities were not entirely safe, for many a soldier or sailor could turn out to be quite brutal.

The sailors' uniform was particularly appreciated for the tight fit and especially for the horizontal fly. Moreover, while soldiers generally had very little time to share, sailors had many weekends. For a walk in the park, a soldier received about 2 shillings ; a silor might get up to 3 pounds. Stephen Tennant wrote about this fascination, nothing one sailor's tight little derière. Anecdotes from those days include the story of an evening organized by Edward Gathorne-Hardy where a contingent of soldiers of the Guard were invited as special guests ; in another, a soldier was offered as a gift to the master of the house. To the soldiers, prostitution was a tradition ; it seems that the young recruits were initiated by the elders as they were being integrated into the regiment. The customers were designated twanks, steamers or fitter's mates. A good patron was preferred ; thus Ackerley reveived a letter one day announcing the death of one of his lovers - and another soldier from his regiment offering himself as a replacement. This part-time prostitution allowed soldiers to get some pocket money, which they then spent on drinks or with prostitutes of their own. These activities were not entirely safe, for many a soldier or sailor could turn out to be quite brutal.from History Of Homosexuality In Europe, 1919-1939 par Florence Tamagne

Proust au bordel

Suite à une dénonciation anonyme, une descente de police eut lieu dans la nuit du 11 au 12 janvier 1918, au 11 rue de l'Arcade dans le huitième arrondissement de Paris. Elle visait l’hôtel Marigny, un garni à double issue, acquis par Albert Le Cuziat en 1917, qualifié par le dénonciateur comme "un lieu de rendez-vous de pédérastes majeurs et mineurs". Le rapport du commissaire Tanguy nous apprend qu'en effet, "le patron de l'hôtel facilitait la réunion d'adeptes de la débauche anti-physique". Bref c'était un bordel. "Des surveillances que j’avait fait exercer avaient confirmé les renseignements que j’avais ainsi recueillis", poursuit le commissaire. "A mon arrivée, j’ai trouvé le sieur Le Cuziat dans un salon du rez-de-chaussée, buvant du champagne avec trois individus aux allures de pédérastes.” Et parmi eux, entre un soldat en convalescence et un caporal de vingt ans et neuf mois en attente d'être réformé (assez grand pour revenir du front mais non pas pour le reste), figure un certain "Proust, Marcel, 46 ans, rentier, 102 Boulevard Haussmann". Puis, dans les chambres, sont découverts plusieurs couples d'hommes, dans lesquels le plus jeune est mineur (la majorité était à vingt et un ans). On peut trouver un écho de cette scène dans un épisode d'Albertine disparue, au cours duquel le narrateur se voit accuser d'"excitation de mineure à la débauche" : "Alors la vie me parut barrée de tous les côtés. Et [...] je trouvai dans la punition qui m’était infligée [...], cette relation qui existe presque toujours dans les châtiments humains et qui fait qu’il n’y a presque jamais ni condamnation juste, ni erreur judiciaire, mais une espèce d’harmonie entre l’idée fausse que se fait le juge d’un acte innocent et les faits coupables qu’il a ignorés". Certes, l'homosexualité n'était pas interdite en France, et il n'y a pas ici d'"outrage public à la pudeur", puisqu'il s'agit d'une maison... close. Mais la consommation d'alcool la nuit (prohibée en ces temps de guerre) et l'habituelle "excitation de mineurs à la débauche" constituaient des chefs d'inculpation suffisants. Aussi le patron, Albert Le Cuziat, sera condamné à quatre mois de prison et 200 francs d'amende. La fermeture de l’établissement fut cependant levée peu après par l’un des puissants qui fréquentaient la maison.

Suite à une dénonciation anonyme, une descente de police eut lieu dans la nuit du 11 au 12 janvier 1918, au 11 rue de l'Arcade dans le huitième arrondissement de Paris. Elle visait l’hôtel Marigny, un garni à double issue, acquis par Albert Le Cuziat en 1917, qualifié par le dénonciateur comme "un lieu de rendez-vous de pédérastes majeurs et mineurs". Le rapport du commissaire Tanguy nous apprend qu'en effet, "le patron de l'hôtel facilitait la réunion d'adeptes de la débauche anti-physique". Bref c'était un bordel. "Des surveillances que j’avait fait exercer avaient confirmé les renseignements que j’avais ainsi recueillis", poursuit le commissaire. "A mon arrivée, j’ai trouvé le sieur Le Cuziat dans un salon du rez-de-chaussée, buvant du champagne avec trois individus aux allures de pédérastes.” Et parmi eux, entre un soldat en convalescence et un caporal de vingt ans et neuf mois en attente d'être réformé (assez grand pour revenir du front mais non pas pour le reste), figure un certain "Proust, Marcel, 46 ans, rentier, 102 Boulevard Haussmann". Puis, dans les chambres, sont découverts plusieurs couples d'hommes, dans lesquels le plus jeune est mineur (la majorité était à vingt et un ans). On peut trouver un écho de cette scène dans un épisode d'Albertine disparue, au cours duquel le narrateur se voit accuser d'"excitation de mineure à la débauche" : "Alors la vie me parut barrée de tous les côtés. Et [...] je trouvai dans la punition qui m’était infligée [...], cette relation qui existe presque toujours dans les châtiments humains et qui fait qu’il n’y a presque jamais ni condamnation juste, ni erreur judiciaire, mais une espèce d’harmonie entre l’idée fausse que se fait le juge d’un acte innocent et les faits coupables qu’il a ignorés". Certes, l'homosexualité n'était pas interdite en France, et il n'y a pas ici d'"outrage public à la pudeur", puisqu'il s'agit d'une maison... close. Mais la consommation d'alcool la nuit (prohibée en ces temps de guerre) et l'habituelle "excitation de mineurs à la débauche" constituaient des chefs d'inculpation suffisants. Aussi le patron, Albert Le Cuziat, sera condamné à quatre mois de prison et 200 francs d'amende. La fermeture de l’établissement fut cependant levée peu après par l’un des puissants qui fréquentaient la maison.

Proust avait rencontré Albert Le Cuziat, ancien valet de chambre du Prince Radziwill et de la comtesse Greffulhe, en 1911 et avait très vite offert à ce "Gotha vivant" de le rémunérer en échange de ses connaissances sur l'étiquette, le protocole, les généalogies, les alliances etc. Autant d'informations qui viendront nourrir les volumes d'A la recherche du temps perdu. Mais Le Cuziat (qui servira de modèle au Jupien du roman) ouvre un établissement de bains, rue Godot-de-Mauroy, puis l'hôtel de la rue de l'Arcade, et il procure alors à l'écrivain des renseignements d'un autre ordre. Et pas seulement des renseignements : des garçons aussi. Céleste Albaret, dans ses souvenirs sur Proust, évoque ce "tenancier de mauvaise maison pour hommes" : "outre que M. Proust me parlait beaucoup de lui et me tenait au courant, j’ai vu moi-même Le Cuziat. Je le dis tout de go : il ne me plaisait pas et je ne le cachais pas à M. Proust. Mais, comme celui-ci était de mon avis, je ne pense pas que mon déplaisir entache l’impartialité de mon jugement. C’était un grand échalas de Breton, blond, sans élégance, avec des yeux bleus, froids comme ceux d’un poisson – les yeux de son âme- et qui portait l’inquiétude de son métier dans le regard et sur le visage. Il avait quelque chose de traqué – rien d’étonnant : il y avait constamment des descentes de police dans son établissement et il faisait souvent de la petite prison." Proust se brouillera ensuite avec Le Cuziat, les deux hommes convoitant, paraît-il, un certain André, concierge du lupanar de la rue de l’Arcade. Céleste Albaret s'en tient à une autre explication plus convenable : Marcel aurait été mécontent de voir les meubles qu'il avait donnés à Le Cuziat intégrés dans le décorum de son bordel - un événement qu'il relate, à peine transposé, dans la Recherche : "Je cessai du reste d’aller dans cette maison parce que désireux de témoigner mes bons sentiments à la femme qui la tenait et avait besoin de meubles, je lui en donnai quelques-uns, notamment un grand canapé — que j’avais hérités de ma tante Léonie. Je ne les voyais jamais car le manque de place avait empêché mes parents de les laisser entrer chez nous et ils étaient entassés dans un hangar. Mais dès que je les retrouvai dans la maison où ces femmes se servaient d’eux, toutes les vertus qu’on respirait dans la chambre de ma tante à Combray, m’apparurent, suppliciées par le contact cruel auquel je les avais livrés sans défense! J’aurais fait violer une morte que je n’aurais pas souffert davantage. Je ne retournai plus chez l’entremetteuse, car ils me semblaient vivre et me supplier, comme ces objets en apparence inanimés d’un conte persan, dans lesquels sont enfermées des âmes qui subissent un martyre et implorent leur délivrance."

Proust avait rencontré Albert Le Cuziat, ancien valet de chambre du Prince Radziwill et de la comtesse Greffulhe, en 1911 et avait très vite offert à ce "Gotha vivant" de le rémunérer en échange de ses connaissances sur l'étiquette, le protocole, les généalogies, les alliances etc. Autant d'informations qui viendront nourrir les volumes d'A la recherche du temps perdu. Mais Le Cuziat (qui servira de modèle au Jupien du roman) ouvre un établissement de bains, rue Godot-de-Mauroy, puis l'hôtel de la rue de l'Arcade, et il procure alors à l'écrivain des renseignements d'un autre ordre. Et pas seulement des renseignements : des garçons aussi. Céleste Albaret, dans ses souvenirs sur Proust, évoque ce "tenancier de mauvaise maison pour hommes" : "outre que M. Proust me parlait beaucoup de lui et me tenait au courant, j’ai vu moi-même Le Cuziat. Je le dis tout de go : il ne me plaisait pas et je ne le cachais pas à M. Proust. Mais, comme celui-ci était de mon avis, je ne pense pas que mon déplaisir entache l’impartialité de mon jugement. C’était un grand échalas de Breton, blond, sans élégance, avec des yeux bleus, froids comme ceux d’un poisson – les yeux de son âme- et qui portait l’inquiétude de son métier dans le regard et sur le visage. Il avait quelque chose de traqué – rien d’étonnant : il y avait constamment des descentes de police dans son établissement et il faisait souvent de la petite prison." Proust se brouillera ensuite avec Le Cuziat, les deux hommes convoitant, paraît-il, un certain André, concierge du lupanar de la rue de l’Arcade. Céleste Albaret s'en tient à une autre explication plus convenable : Marcel aurait été mécontent de voir les meubles qu'il avait donnés à Le Cuziat intégrés dans le décorum de son bordel - un événement qu'il relate, à peine transposé, dans la Recherche : "Je cessai du reste d’aller dans cette maison parce que désireux de témoigner mes bons sentiments à la femme qui la tenait et avait besoin de meubles, je lui en donnai quelques-uns, notamment un grand canapé — que j’avais hérités de ma tante Léonie. Je ne les voyais jamais car le manque de place avait empêché mes parents de les laisser entrer chez nous et ils étaient entassés dans un hangar. Mais dès que je les retrouvai dans la maison où ces femmes se servaient d’eux, toutes les vertus qu’on respirait dans la chambre de ma tante à Combray, m’apparurent, suppliciées par le contact cruel auquel je les avais livrés sans défense! J’aurais fait violer une morte que je n’aurais pas souffert davantage. Je ne retournai plus chez l’entremetteuse, car ils me semblaient vivre et me supplier, comme ces objets en apparence inanimés d’un conte persan, dans lesquels sont enfermées des âmes qui subissent un martyre et implorent leur délivrance." Après la guerre, Le Cuziat ouvrira un nouvel établissement, rue Saint-Augustin. Maurice Sachs situe Les Bains du Ballon d'Alsace rue Saint-Lazare, tandis qu'il s'attarde, dans Le Sabbat, sur leur description. Un établissement "qui, sous couvert d'un commerce de bains, dissimulait celui des prostitués mâles, garçons assez veules, trop paresseux pour chercher un travail régulier, et qui gagnaient l'argent qu'ils rapportaient à leurs femmes en couchant avec des hommes." On y entre par une "cour pavée, décorée de lauriers en caisse et de troènes comme celle d’un presbytère, avec un petit perron de quatre marches, l’étroite marquise et le mot Bains sur la porte vitrée." Sachs est un client assidu et se lie d'amitié avec le patron, qui le régale de ragots et d'histoires salaces sur l'auteur d'A la recherche du temps perdu. Venir dans un bordel dont le vestibule s'orne de meubles donnés par Proust flatte le snobisme de Sachs : "Ce n'était pas le moindre attrait qu'avait pour moi cet étrange établissement que d'y retrouver, au-delà de sa mort, mais terriblement vivant, ce Marcel Proust dont le nom avait été pour notre jeunesse comme un gage de féerie."